Winter Climbing

Photo above: Now to get down! Colin Wells admires the end of day light on Great Gable after an ascent of Moss Ghyll (IV), Scafell.

These notes are intended to assist the climber who has already gained considerable knowledge of rock climbing and is fully aware of its risks but still wishes to progress into winter mountaineering. They are brief and not designed to be comprehensive in any way. Ultimately climbing is a dangerous sport and claims many casualties each year. One of the guiding principals of British climbing and mountaineering is that it is the individual climber is responsible for his or her own safety. If you cannot accept this then this site and probably climbing in general is unlikely to suit you. May we refer you to this very interesting site instead!

If you are still determined to venture into the Highlands in winter then Mountaineering Scotland's Winter Mountaineering in Scotland is worth reading, as is the BMC's Essential Winter Know-How.

Plas y Brenin administers the Conville Trust which provides subsidised Winter Skills courses for young impoverished climbers.

Check out the latest Scottish Winter Conditions.

In the notes below we frequently refer to "Scottish" winter climbing or "Scottish" mixed. Of course, with the wealth of winter climbing in England and Wales, this should really be British, but the term "Scottish" seems to have stuck.

Ice climbing gear has improved enormously in recent years. It has also become considerably more specialised; to the extent that one now has to ask exactly what sort of winter routes one intends to do before choosing the appropriate kit.

Basic Scottish Winter Climbing (Up to Grade III)

Crampons: Semi-rigid 12 point crampons are ideal. These are stiff enough for climbing yet still flexible enough to be comfortable when walking, and do not ball up too badly. Models such as the Grivel Air Tech are ideal for those who are wanting a crampon for walking as much as climbing as its short points make it a better choice on rough ground. Choosing the New Classic binding option will mean you can put it on just about any boot.

Axes: At this sort of grade, straight-shafted tools (or very slightly curved tools) such as the BD Venom are a good choice if you are only likely to be climbing in UK and alpine mountaineering - they are certainly easier to use in confined spaces such as chimneys and when plunging the shafts into snow or "daggering" with the ferules (the points on the bottoms of the shafts - common techniques on easier pitches. Leashes are not much of a problem at this grade and for the Alps are probably worth having.

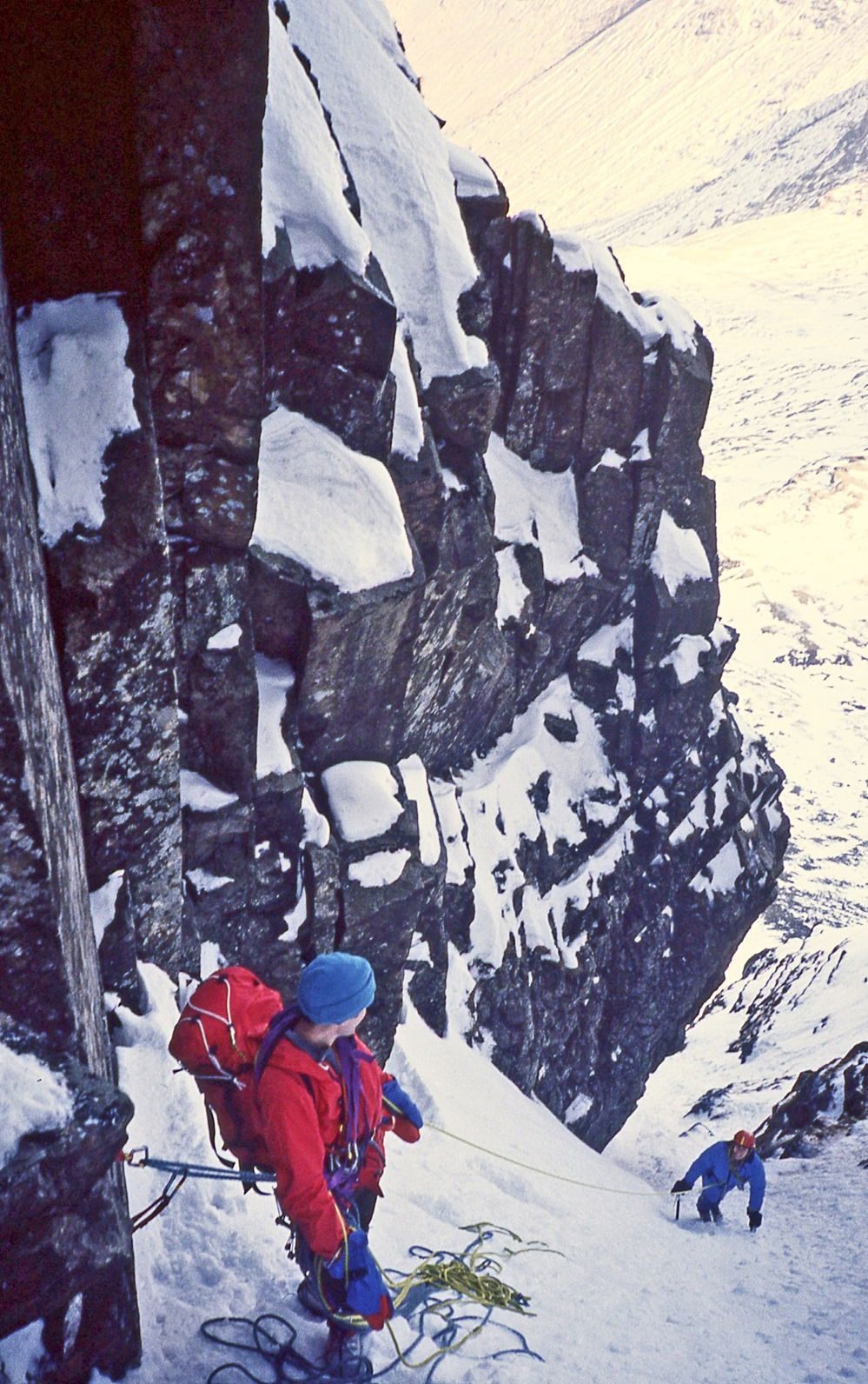

Above: Stephen and Jilly Reid climbing Central Gully on Great End, a classic grade II in the Lake District (the terms Scottish Winter and Scottish Mixed equally apply to routes elsewhere in the UK). Note that on this straightforward lower section of the route the leader is belaying the second using a back belay which is quicker to take in on easy ground than using a belay plate.

Above: Dave Bodecott tackling steep ice on the third pitch of Minus One Gully (VI), Ben Nevis. When in condition, which is not often, this route is almost pure water ice the whole way. However it finishes half way up North East Buttress (IV) which is a mixed climb of considerable difficulty.

Advanced Scottish Winter Climbing (Grade IV and above)

Crampons: Fully rigid crampons may be preferred by some as they give firmer placements when front-pointing and less wobble on tiny rock holds. However, they are rather uncomfortable as walking crampons and Scottish mixed tends to involve a lot of walking. Semi-rigid crampons such as the Grivel G14 are better for walking and have the advantage of forged front points that can be set as mono-points. This makes them ideal for all aspects of winter mountaineering from grade I gullies to harder mixed climbs, and they are good for steep water ice too. In mono-point set up they are particularly good on buttress climbs as a single point will go into a crack where two points won’t.

Axes: For steep ice and buttress climbs a pair of bent-shafted axes give a distinct advantage. The choice is between ultra modern leashless tools such as the Petzl Nomic and the Black Diamond Hydra that have no adze or hammer (though in some cases these can be retro-fitted) and slightly more traditional but still leashless tools such as the DMM Apex and the Petzl Quark that come equipped with adze and hammer. Whilst the former are widely acknowledge to be the best choice for super-steep ice and buttress climbs, the lack of adze and hammer is likely to be a nuisance on more traditional mountain and alpine routes. If in doubt we’d suggest the latter, which also have the advantage that they can be fitted with clipper leashes if desired. Also, when considering what to buy, it is noteworthy that anything with too light a head is a pain if you are trying to hammer a peg into a crack or an icehook or warthog into frozen turf. On multipitch climbs a set of Axe Lanyards (aka spring leashes) are well worth the money as dropping an axe 6 pitches up Orion Direct will not be funny for you or anyone below you!

Above: Stephen Reid, belayed by Steve Prior, thrutching his way up the final pitch of Savage Slit (V), Coire an Lochan, Cairngorms. This is a completely mixed climb, ie a mixture of rock, ice and snow with many moves involving twisting (or torqueing) various parts of one's axes in cracks. (photo Andy Perkins).

Continental-type Icefalls

Crampons: While standard crampons will do, crampons with forged front points are a great advantage on steep ice where they penetrate better.

Axes: Bent-shafted leashless axes such as the DMM Cortex and Grivel Tech Machine make climbing steep ice a grade easier than it would be with more traditional axes. It's a bit like learning to hand-jam - once you have learned to relax, it all seems a lot easier. If going leashless on multi-pitch, consider using a special set of Axe Lanyards (aka spring leashes) to prevent the embarrassment of dropping a tool!

Above: Colin Wells - steep on a frozen sea - Trappfoss (WI4), Rjukan, Norway, a mecca for water ice climbers where ice-screws and slings provide protection and rock gear is not needed on most routes.

Other Kit

Boots: Fully stiffened boots with a good level of insulation, are essential. Contrary to popular belief, it is not necessary that the uppers are completely stiff and modern fabric winter boots are considerably more comfortable to walk in as a result.

Harness: A harness that you can put on without lifting your feet off the ground is a useful investment.

Rack: Take a fairly full rack, but not as extensive as you would for a technical summer rock climb. Although the perpetuated wisdom is that cams are useless in winter, this is not always the case, particularly on Cairngorm granite. However, some large nuts should be carried as well. Slings become more useful than ever - take lots.

Pegs: A small bunch should always be carried, especially in icy conditions where cracks may be iced up, and particularly on the Ben, where they always seem to be needed. A good selection would be 2 x blades, 1 x kingpin, 1 x channel.

Ice-Screws: Essential on many routes of grade III and above. At least four should be carried, one for each belay and two as runners. Modern sharp ones with wind-in handles are a fantastic improvement compared with what was available in the 1980s. A Warthog or two can be useful on frozen turf.

Abalakov Threader: Learn how to place an Abalakov Thread and you can abseil your way out of all sorts of trouble. You’ll also need several metres of thin cord or tape and a knife.

Ice Hooks: Despite the name, these are mainly used in iced up corner cracks and in shallow frozen turf placements where they work well in that you can get something in places where you otherwise wouldn't. Probably the most dangerous bit of gear to have on your harness if you fall off!

Warthogs: Originally designed as an icescrew, it is worth carrying at least one of these for frozen turf belays.

Helmet: Essential for all winter and alpine climbing as stones and ice can be knocked down by other parties at any time.

Headtorch: You'll be lost without one! Ditto a Map and Compass – don’t rely just on your phone and/or GPS, useful aids though these can be.

Bivi Bag: If you do get lost (and/or injured), you may well need one - make it light but breathable (rather than the emergency type) if you plan to use it for snow holing and bothies. Also spare food and clothing. It's worth considering a lightweight 4 person Group Survival Shelter as well.

If the climber in the photo looks a bit sheepish it is because he has just ridden several hundred feet down Creag Meagaidh on the avalanche behind him. The photographer was with him too - hence the camera shake. Be careful out there!

The Divine Mysteries of the Oromaniacal Quest

And what joy, think ye, did they feel after the exceeding long and troublous ascent? - after

Scrambling, slipping

Pulling, pushing

Lifting, gasping

Looking, hoping

Despairing, climbing

Holding on, falling off

Trying, puffing,

Loosing, gathering,

Talking, stepping,

Grumbling, anathematising

Scraping, hacking

Bumping, jogging

Overturning, hunting

Straddling, -

for know you that by these methods alone are the most divine mysteries of the Quest reached. |

| Norman Collie |